Solar power

شمسی توانائی

انسانی زندگی کی نقل و حرکت کا خاصا انحصار توانائی پر ہے۔ آج جس بڑے پیمانے پر توانائی کا استعمال ہو رہا ہے اس سے خدشہ یہ ہے کہ توانائی کے ذخائر بہت دنوں تک ہمارا ساتھ نہیں دے سکیں گے۔ توانائی کے یہ ذخائر اور ذرائع ماحول کو بھی آلودہ کر رہے ہیں۔ ہمیں توانائی کے نئے متبادل تلاش کرنے ہوںگے تاکہ توانائی کے ساتھ ساتھ ماحول کو بھی آلودگی سے بچایا جاسکے اور یہ تبھی ممکن ہے جب ہم تیل، کوئلہ، لکڑی اور گوبر کے علاوہ دھوپ، ہوا، پانی اور دیگر توانائی کے قدرتی ذرائع کا استعمال کریں۔ مزید برآں شمسی توانائی جو کبھی نہ ختم ہونے والا ذریعہ ہے۔ روایتی توانائی کے ذرائع ہیں کوئلہ، معدنی تیل، لکڑی اور گوبر وغیرہ جب کہ غیر روایتی توانائی حاصل کرنے کے ذرائع ہیں شمسی توانائی، آبی یا موجی توانائی، ہوائی توانائی،پودوں سے پٹرول کشید کرکے توانائی حاصل کرنا، جوہری توانائی، بائیو گیس اور ارضی حرارتی توانائی۔ کوئلہ، معدنی تیل اور برقاب— توانائی حاصل کرنے کے تین اہم وسائل ہیں جن میں جوہری توانائی کا اضافہ ابھی حال میں ہوا ہے۔ کوئلہ توانائی کے حصول یا صنعتی ایندھن کا سب سے بڑا وسیلہ ہے۔ کوئلے کی تین قسمیں ہیں۔ اینتھرا سائیٹ، بِیٹُومینس، اور لگنائیٹ۔ ان سب میں سب سے عمدہ قسم اینھتراسائیٹ کی ہوتی ہے جس میں دھواں کم نکلتا ہے اور بہت گرمی دیتا ہے۔ دوسری قسم میں دھواں نسبتاً زیادہ نکلتا ہے مگر یہ بھی کافی گرمی دیتا ہے۔ تیسری قسم میں آنچ کم اور دھواں بہت ہوتا ہے۔ بجلی پیدا کرنے کے لیے ان کا استعمال کیا جاتا ہے۔ کوئلے کے علاوہ قدرتی تیل یا پٹرولیم توانائی حاصل کرنے کا دوسرا ذریعہ ہے۔ اور یہ نہایت کار آمد ایندھن بھی ہے۔ کچے قدرتی تیل سے ہمیں مٹی کا تیل، ڈیزل، پٹرول، اسپرٹ، کھانا پکانے کی گیس وغیرہ حاصل ہوتی ہے۔ ہماری روزانہ کی زندگی میں قدرتی تیل اور اس سے بنی ہوئی اشیا کی بہت ضرورت ہوتی ہے۔ اسکوٹر، موٹر سائیکل، کار، بسیں، ریل گاڑیاں، جہاز، ہوائی جہاز ملیں اور فیکٹریاں وغیرہ پٹرول اور ڈیزل سے چلتے ہیں۔ غرض یہ کہ قدرتی تیل یا پٹرولیم ہماری معاشی زندگی کی شہہ رگ ہے۔ زمین کی گہرائیوں میں حرارت کا بے شمار خزانہ دفن ہے۔ ماہرین ارضیات کے مطابق زمین کی اس پپڑی کے نیچے درجہ ¿ حرارت 7200oF یعنی 4000 سینٹی گریڈ ہے۔ حرارت اکثر آتش فشانو ںکے علاوہ زمین کے مختلف حصوں سے خارج ہونے والی بھاپ کی شکل میں بھی ظاہر ہوتی رہتی ہے۔ 1904 میں Geo-Thermal Energy کو کام میں لانے کا منصوبہ تیار کیا گیا تھا۔ زمین کے اندر کی بھاپ کو پائپ کے ذریعے چرخاب تک لایا گیا اور اس سے بجلی پیدا کی گئی۔ زمین اندر سے بہت گرم ہے اور اس میں جگہ جگہ پر گرم پانی کی دھار یا سوکھی بھاپ کی تیز دھار پھوٹتی رہتی ہے۔ اس حرارت کو اگر توانائی میں بدل دیا جائے تو ہزاروں سال تک توانائی کا مسئلہ حل ہو سکتا ہے۔کوئلہ سے پٹرول بنانے کا طریقہ جنوبی افریقہ میں شروع ہوا۔ وہاں کوئیلے کی کانیں وافر مقدار میں کوئلہ فراہم کر سکتی ہیں مگر یہ طریقہ بہت مہنگا ہے اور اس میں کوئلے کی کھپت بہت زیادہ ہوتی ہے۔کوڑا کرکٹ سے بھی توانائی پیدا کی جا سکتی ہے۔ ماہرین کے مطابق امریکہ میں سالانہ 25 کروڑ ٹن کوڑا پھینکا جاتا ہے۔ اس سے دس کروڑ ٹن کوئلے کے برابر توانائی حاصل کی جاسکتی ہے۔پودوں سے بھی پٹرول حاصل کیا جاتا ہے۔ ماہرین کی تحقیق کے مطابق گنے کے رس سے الکوہل (Alcohal) بنائی جاتی ہے اور اس الکوہل کو بطور پٹرول استعمال کرکے گاڑی چلائی جاسکتی ہے۔ دنیا بھر میں پودوں سے الکوہل کا سب سے زیادہ ایندھن پیدا کرنے والا ملک برازیل ہے کیونکہ وہاں گنا بہت پیدا ہوتا ہے۔ اس تکنیک کا ہمارے ملک میں بھی استعمال ہورہا ہے۔ عہد حاضر کے سائنس داں سورج کی روشنی سے توانائی حاصل کرنے کے تجربات میں مصروف ہیں اور کافی حد تک انھیں کامیابی بھی حاصل ہوئی ہے۔ ہوا کی طاقت کا استعمال دنیا کے کچھ ممالک نے آٹے کی چکیوں کو چلاکر کیا ہے۔ بہتے ہوئے پانی کوباندھ کے ذریعے روک کر بہت اونچائی سے گرا کر بجلی پیدا کرتے ہیں۔ اگر سائنسی ترقی اسی رفتار سے ہوتی رہی تو وہ دن دور نہیں جب سورج کی روشنی سے طاقت حاصل کرکے ہر وہ کام کیا جائے گا جو آج قدرتی تیل سے ہو رہا ہے اور جس کے ذخائر محدود ہیں۔شمسی توانائی کبھی نہ ختم ہونے والی توانائی ہے۔

شمسی توانائی

سورج کی دھوپ اپنے آپ میں آلودگی سے پاک ہے اور بہ آسانی میسر ہے۔ ہندوستان کو یہ سہولت حاصل ہے کہ سال کے 365 دنوں میں 250 سے لے کر 320 دنوں تک سورج کی پوری دھوپ ملتی رہتی ہے۔ دن میں سورج چاہے دس سے بارہ گھنٹے تک ہی ہمارے ساتھ رہے لیکن یہ حقیقت ہے کہ سورج کی گرمی ہمیں رات دن کے 24 گھنٹے حاصل ہو سکتی ہے۔ اس میں نہ دھواں ہے، نہ کثافت اور نہ ہی آلودگی۔ دیگر ذرائع سے حاصل توانائی کے مقابلے میں سورج کی روشنی سے 36 گنا زیادہ توانائی حاصل ہوسکتی ہے۔ جب کہ صورت حال یہ ہے کہ سورج کی روشنی کرنوں کی شکل میں صرف چوتھائی حصہ ہی زمین پر آتی ہے اور تین چوتھائی حصہ کرہ ¿ باد میں ہی رہ جاتی ہے۔سورج اپنی توانائی X-Ray سے لے کر Radio-Wave کے ہر Wave-Length پر منعکس کرتا ہے۔ اسپکٹرم (Spectrum) کے 40فیصد حصے پر یہ توانائی نظر آتی ہے اور 50 فیصد شمسی توانائی انفرا ریڈ (Infra-Red) اور بقیہ Ultra-Violet کی شکل میں نمودار ہوتی ہے۔دھوپ سے حاصل ہونے والی توانائی ”سولر انرجی“ یا ”شمسی توانائی“ کہلاتی ہے۔ دھوپ کی گرمی کو پانی سے بھاپ تیار کرکے جنریٹر چلانے اور بجلی بنانے میں بھی استعمال کیا جا سکتا ہے۔ دھوپ قدرت کا عطیہ ہے، ہر روز دنیا پر اتنی دھوپ پڑتی ہے کہ اس سے کئی ہفتوں کے لیے بجلی تیار کی جا سکتی ہے۔ سورج زمین سے تقریباً 15کروڑ کلومیٹر کے فاصلے پر واقع ہے۔ یہ زمین سے تیرہ لاکھ گنا بڑا ہے۔ چونکہ آفتاب میں صرف تپتی ہوئی گیس پائی جاتی ہے، اس لیے اس کی کثافت (Density) کم ہے۔ اس کا وزن زمین سے سوا تین لاکھ گنا زیادہ ہے۔ سورج کی باہری سطح کا درجہ ¿ حرارت تقریباً 6ہزار ڈگری سیلسیس ہے۔ اس کے مرکزی حصے کا درجہ ¿ حرارت ایک کروڑ ڈگری Celcius ہے۔ اس کے چاروں طرف روشنی اور حرارت نکلتی رہتی ہے۔ سورج کی سطح کے فی مربع سینٹی میٹر سے پچاس ہزار موم بتیوں جتنی روشنی نکلتی ہے اور زمین سورج سے نکلی ہوئی طاقت کا محض دوسو بیس کروڑواں حصہ ہی اخذکر پاتی ہے۔ شمسی توانائی کے بغیر زمین پر زندگی ممکن نہیں۔ سبز پتیوں والے پودے اس طاقت کا استعمال کرتے ہیں جس کے باعث ان میں Photosynthesis کا عمل ہوتا ہے۔

استعمالات کے میدان

آج شمسی توانائی سے بہت سے کام لیے جا رہے ہیں۔ چاہے کھانا پکانا ہو، پانی گرم کرنا ہو یا مکانوں کو ٹھنڈا یا گرم رکھنا ہو۔ فصلوں کے دنوں میں دھان سکھانا ہو یا پائپوں کے ذریعے سینچائی۔ دہلی کے نزدیک گوالی پہاڑی میں سورج سے بجلی کی توانائی حاصل کرنے کے لیے ایک بجلی گھر بنایا گیا ہے جہاں پیداوار اور تحقیقی کام کیے جا رہے ہیں۔ ملک کے دیگر حصوں میں Solar Photovoltaic Centres قائم کیے جا چکے ہیں جو ایک کلوواٹ سے ڈھائی کلوواٹ تک بجلی پیدا کرتے ہیں۔ گھروں، ڈیریوں، کارخانوں، ہوٹلوں اور اسپتالوں میں پانی گرم کرنے کے لیے ایسے آلات لگے ہیں جو 100 لیٹر سے لے کر سوا لاکھ لیٹر تک پانی گرم کر سکتے ہیں۔ شمسی چولھے کم سے کم دو کلو لکڑی کی بچت کر سکتے ہیں۔ ہندوستان میں اگر 17 کروڑ خاندان مان لیے جائیں تو روزانہ کم از کم 34 کروڑ کلو لکڑی کی بچت کی جا سکتی ہے۔ ان اقدامات کو دیکھتے ہوئے ہم یہ کہہ سکتے ہیں کہ ہمارا ملک غیرروایتی توانائی کے میدان میں داخل ہو چکا ہے اورتوانائی حاصل کرنے کا مستقبل اب دھوپ، سمندر کے پانی اور ایک قسم کی ایٹمی توانائی جو کہ Nuclear Fusion کہلاتی ہے، جیسے ذرائع سے وابستہ ہوتا جا رہاہے۔

The PS10 concentrates sunlight from a field of heliostats on a central tower.

| Renewable energy |

|---|

| Biofuel Biomass Geothermal Hydroelectricity Solar energy Tidal power Wave power Wind power |

| v · d · e |

Solar power is the conversion of sunlight into electricity, either directly using photovoltaics (PV), or indirectly using concentrated solar power (CSP). Concentrated solar power systems use lenses or mirrors and tracking systems to focus a large area of sunlight into a small beam. Photovoltaics convert light into electric current using the photoelectric effect.[1]

Commercial concentrated solar power plants were first developed in the 1980s, and the 354 MW SEGS CSP installation is the largest solar power plant in the world and is located in the Mojave Desert of California. Other large CSP plants include the Solnova Solar Power Station (150 MW) and the Andasol solar power station (100 MW), both in Spain. The 97 MW Sarnia Photovoltaic Power Plant in Canada, is the world’s largest photovoltaic plant.

Applications

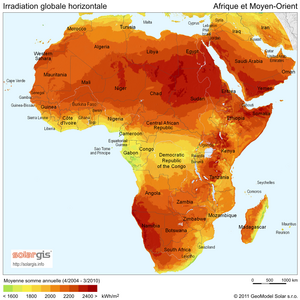

Average insolation showing land area (small black dots) required to replace the world primary energy supply with solar electricity. 18 TW is 568 Exajoule (EJ) per year. Insolation for most people is from 150 to 300 W/m² or 3.5 to 7.0 kWh/m²/day.

Solar power is the conversion of sunlight into electricity. Sunlight can be converted directly into electricity using photovoltaics (PV), or indirectly with concentrated solar power (CSP), which normally focuses the sun’s energy to boil water which is then used to provide power, and other technologies, such as the sterling engine dishes which use a sterling cycle engine to power a generator. Photovoltaics were initially used to power small and medium-sized applications, from the calculator powered by a single solar cell to off-grid homes powered by a photovoltaic array.

The only significant problem with solar power is installation cost, although cost has been decreasing due to the learning curve.[2] Developing countries in particular may not have the funds to build solar power plants, although small solar applications are now replacing other sources in the developing world.[3][4]

Concentrating solar power

Solar troughs are the most widely deployed.

Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) systems use lenses or mirrors and tracking systems to focus a large area of sunlight into a small beam. The concentrated heat is then used as a heat source for a conventional power plant. A wide range of concentrating technologies exists; the most developed are the parabolic trough [discuss], the concentrating linear fresnel reflector, the Stirling dish and the solar power tower. Various techniques are used to track the Sun and focus light. In all of these systems a working fluid is heated by the concentrated sunlight, and is then used for power generation or energy storage.[5]

A parabolic trough consists of a linear parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned along the reflector’s focal line. The receiver is a tube positioned right above the middle of the parabolic mirror and is filled with a working fluid. The reflector is made to follow the Sun during the daylight hours by tracking along a single axis. Parabolic trough systems provide the best land-use factor of any solar technology.[6] The SEGS plants in California and Acciona’s Nevada Solar One near Boulder City, Nevada are representatives of this technology.[7][8] Compact Linear Fresnel Reflectors are CSP-plants which use many thin mirror strips instead of parabolic mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto two tubes with working fluid. This has the advantage that flat mirrors can be used which are much cheaper than parabolic mirrors, and that more reflectors can be placed in the same amount of space, allowing more of the available sunlight to be  used. Concentrating linear fresnel reflectors can be used in either large or more compact plants.[9][10]

used. Concentrating linear fresnel reflectors can be used in either large or more compact plants.[9][10]

The Stirling solar dish combines a parabolic concentrating dish with a Stirling engine which normally drives an electric generator. The advantages of Stirling solar over photovoltaic cells are higher efficiency of converting sunlight into electricity and longer lifetime. Parabolic dish systems give the highest efficiency among CSP technologies.[11] The 50 kW Big Dish in Canberra, Australia is an example of this technology.[7]

A solar power tower uses an array of tracking reflectors (heliostats) to concentrate light on a central receiver atop a tower. Power towers are more cost effective, offer higher efficiency and better energy storage capability among CSP technologies.[7] The Solar Two in Barstow, California and the Planta Solar 10 in Sanlucar la Mayor, Spain are representatives of this technology.[7][12]

Photovoltaics

The 71.8 MW Lieberose Photovoltaic Park in Germany.

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell (PV), is a device that converts light into electric current using the photoelectric effect. The first solar cell was constructed by Charles Fritts in the 1880s.[13] In 1931 a German engineer, Dr Bruno Lange, developed a photo cell using silver selenide in place of copper oxide.[14] Although the prototype selenium cells converted less than 1% of incident light into electricity, both Ernst Werner von Siemens and James Clerk Maxwell recognized the importance of this discovery.[15] Following the work of Russell Ohl in the 1940s, researchers Gerald Pearson, Calvin Fuller and Daryl Chapin created the silicon solar cell in 1954.[16] These early solar cells cost 286 USD/watt and reached efficiencies of 4.5–6%.[17]

Development and deployment

Nellis Solar Power Plant, 14 MW power plant installed 2007 in Nevada, USA

The early development of solar technologies starting in the 1860s was driven by an expectation that coal would soon become scarce. However, development of solar technologies stagnated in the early 20th century in the face of the increasing availability, economy, and utility of coal and petroleum.[18] In 1974 it was estimated that only six private homes in all of North America were entirely heated or cooled by functional solar power systems.[19] The 1973 oil embargo and 1979 energy crisis caused a reorganization of energy policies around the world and brought renewed attention to developing solar technologies.[20][21] Deployment strategies focused on incentive programs such as the  Federal Photovoltaic Utilization Program in the US and the Sunshine Program in Japan. Other efforts included the formation of research facilities in the US (SERI, now NREL), Japan (NEDO), and Germany (Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE).[22]

Federal Photovoltaic Utilization Program in the US and the Sunshine Program in Japan. Other efforts included the formation of research facilities in the US (SERI, now NREL), Japan (NEDO), and Germany (Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE).[22]

Between 1970 and 1983 photovoltaic installations grew rapidly, but falling oil prices in the early 1980s moderated the growth of PV from 1984 to 1996. Since 1997, PV development has accelerated due to supply issues with oil and natural gas, global warming concerns, and the improving economic position of PV relative to other energy technologies.[23] Photovoltaic production growth has averaged 40% per year since 2000 and installed capacity reached 10.6 GW at the end of 2007,[24] and 14.73 GW in 2008.[25] As of November 2010, the largest photovoltaic (PV) power plants in the world are the Finsterwalde Solar Park (Germany, 80.7 MW), Sarnia Photovoltaic Power Plant (Canada, 80 MW), Olmedilla Photovoltaic Park (Spain, 60 MW), the Strasskirchen Solar Park (Germany, 54 MW), the Lieberose Photovoltaic Park (Germany, 53 MW), and the Puertollano Photovoltaic Park (Spain, 50 MW).[26]

PV power station |

Country |

DC peak power (MWp)  |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarnia Photovoltaic Power Plant[27] | Canada | 97[26] | Constructed 2009-2010[28] |

| Montalto di Castro Photovoltaic Power Station[26] | Italy | 84.2 | Constructed 2009-2010 |

| Finsterwalde Solar Park[29][30] | Germany | 80.7 | Phase I completed 2009, phase II and III 2010 |

| Rovigo Photovoltaic Power Plant[31][32] | Italy | 70 | Completed November 2010 |

| Olmedilla Photovoltaic Park | Spain | 60 | Completed September 2008 |

| Strasskirchen Solar Park | Germany | 54 | |

| Lieberose Photovoltaic Park [33][34] | Germany | 53 | Completed in 2009 |

| Puertollano Photovoltaic Park | Spain | 50 | 231,653 crystalline silicon modules, Suntech and Solaria, opened 2008 |

Commercial concentrating solar thermal power (CSP) plants were first developed in the 1980s. The 11 MW PS10 power tower in Spain, completed in late 2005, is Europe’s first commercial CSP system, and a total capacity of 300 MW is expected to be installed in the same area by 2013.[35] When built, the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility in southeastern California near the Nevada border is expected to have a capacity of 392 Megawatts.

| Capacity (MW)  |

Name |

Country |

Location |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 354 | Solar Energy Generating Systems | Mojave Desert California | Collection of 9 units | |

| 150 | Solnova Solar Power Station | Seville | Completed 2010 [36][37][38][39][40] |

|

| 100 | Andasol solar power station | Granada | Completed 2009 [41][42] |

|

| 64 | Nevada Solar One | Boulder City, Nevada | ||

| 50 | Ibersol Ciudad Real | Puertollano, Ciudad Real | Completed May 2009 [43] | |

| 50 | Alvarado I | Badajoz | Completed July 2009 [44][45][46] | |

| 50 | Extresol 1 | Torre de Miguel Sesmero (Badajoz) | Completed February 2010 [47][48][49] | |

| 50 | La Florida | Alvarado (Badajoz) | completed July 2010 [47][50] |

Economics

The U.S. Energy Information Administration calculates that, all-told, electricity from a Solar PV plants costs 4 times that of conventional coal.[51] Bloomberg New Energy Finance in March 2011, put the 2010 cost of solar panels at $1.80 per watt, but estimated that the price would decline to $1.50 per watt by the end of 2011.[52] Nevertheless, there are exceptions– Nellis Air Force Base is receiving photoelectric power for about 2.2 ¢/kWh and grid power for 9 ¢/kWh.[53][54] Also, since PV systems use no fuel and modules typically last 25 to 40 years, the International Conference on Solar Photovoltaic Investments, organized by EPIA, has estimated that PV systems will pay back their investors in 8 to 12 years.[55] As a result, since 2006 it has been economical for investors to install photovoltaics for free in return for a long term power purchase agreement. Fifty percent of commercial systems were installed in this manner in 2007 and it is expected that 90% will by 2009.[56]

Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) facilities produce power more cheaply than photovoltaic systems and may eventually be price-competitive with conventional power plants. The Ivanpah Solar Power Facility is expected to produce power at costs comparable to natural gas.[57]

Additionally, governments have created various financial incentives to encourage the use of solar power. Renewable portfolio standards impose a government mandate that utilities generate or acquire a certain percentage of renewable power regardless of increased energy procurement costs. In most states, RPS goals can be achieved by any combination of solar, wind, biomass, landfill gas, ocean, geothermal, municipal solid waste, hydroelectric, hydrogen, or fuel cell technologies.[57] In Canada, the Renewable Energy Standard Offer Program (RESOP), introduced in 2006[58] and updated in 2009 with the passage of the Green Energy Act, allows residential homeowners in Ontario with solar panel installations to sell the energy they produce back to the grid (i.e., the government) at 42¢/kWh, while drawing power from the grid at an average rate of 6¢/kWh.[59] The program is designed to help promote the government’s green agenda and lower the strain often placed on the energy grid at peak hours. In March, 2009 the proposed FIT was increased to 80¢/kWh for small, roof-top systems (≤10 kW).[60]

One financial disincentive to solar power is the large land area required. A 1000 Megawatt CSP facility requires 6000 acres of land while a similar coal-fired plant requires less than 640 acres of land. Producing 1000 Megawatts from photovoltaics requires over 12,000 acres of land.[61] In the US, power companies may avoid purchasing land by leasing  public land from the federal government to develop solar power facilities; however this entails different costs such as rental fees, megawatt surcharges, and the cost of compliance with a complex and time-consuming federal permitting process.[62]

public land from the federal government to develop solar power facilities; however this entails different costs such as rental fees, megawatt surcharges, and the cost of compliance with a complex and time-consuming federal permitting process.[62]

Energy storage methods

This energy park in Geesthacht, Germany, includes solar panels and pumped-storage hydroelectricity.

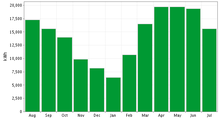

Seasonal variation of the output of the solar panels at AT&T Park in San Francisco

Solar energy is not available at night, making energy storage an important issue in order to provide the continuous availability of energy.[63] Both wind power and solar power are intermittent energy sources, meaning that all available output must be taken when it is available and either stored for when it can be used, or transported, over transmission lines, to where it can be used. Wind power and solar power tend to be somewhat complementary, as there tends to be more wind in the winter and more sun in the summer, but on days with no sun and no wind the difference needs to be made up in some manner.[64] The Institute for Solar Energy Supply Technology of the University of Kassel pilot-tested a combined power plant linking solar, wind, biogas and hydrostorage to provide load-following power around the clock, entirely from renewable sources.[65]

Solar energy can be stored at high temperatures using molten salts. Salts are an effective storage medium because they are low-cost, have a high specific heat capacity and can deliver heat at temperatures compatible with conventional power systems. The Solar Two used this method of energy storage, allowing it to store 1.44 TJ in its 68 m³ storage tank, enough to provide full output for close to 39 hours, with an efficiency of about 99%.[66]

Off-grid PV systems have traditionally used rechargeable batteries to store excess electricity. With grid-tied systems, excess electricity can be sent to the transmission grid. Net metering programs give these systems a credit for the electricity they deliver to the grid. This credit offsets electricity provided from the grid when the system cannot meet demand, effectively using the grid as a storage mechanism. Credits are normally rolled over month to month and any remaining surplus settled annually.[67]

Pumped-storage hydroelectricity stores energy in the form of water pumped when surplus electricity is available, from a lower elevation reservoir to a higher elevation one. The energy is recovered when demand is high by releasing the water: the pump becomes a turbine, and the motor a hydroelectric power generator.[68]

Artificial photosynthesis involves the use of nanotechnology to store solar electromagnetic energy in chemical bonds, by splitting water to produce hydrogen fuel or then combining with carbon dioxide to make biopolymers such as methanol. Many large national and regional research projects on artificial photosynthesis are now trying to develop techniques integrating improved light capture, quantum coherence methods of electron transfer and cheap catalytic materials that operate under a variety of atmospheric conditions.[69]

Experimental solar power

Concentrated photovoltaics (CPV) systems employ sunlight concentrated onto photovoltaic surfaces for the purpose of electrical power production. Solar concentrators of all varieties may be used, and these are often mounted on a solar tracker in order to keep the focal point upon the cell as the Sun moves across the sky.[70] Luminescent solar concentrators (when combined with a PV-solar cell) can also be regarded as a CPV system. Luminescent solar concentrators are useful as they can improve performance of PV-solar panels drastically.[71]

Thermoelectric, or "thermovoltaic” devices convert a temperature difference between dissimilar materials into an electric current. First proposed as a method to store solar energy by solar pioneer Mouchout in the 1800s,[72] thermoelectrics reemerged in the Soviet Union during the 1930s. Under the direction of Soviet scientist Abram Ioffe a concentrating system was used to thermoelectrically generate power for a 1 hp engine.[73] Thermogenerators were later used in the US space program as an energy conversion technology for powering deep space missions such as Cassini, Galileo and Viking. Research in this area is focused on raising the efficiency of these devices from 7–8% to 15–20%.[74]

Space-based solar power is a theoretical design for the collection of solar power in space, for use on Earth. SBSP differs from the usual method of solar power collection in that the solar panels used to collect the energy would reside on a satellite in orbit, often referred to as a solar power satellite (SPS), rather than on Earth’s surface. In space, collection of the Sun’s energy is unaffected by the day/night cycle, weather, seasons, or the filtering effect of Earth’s atmospheric gases. Average solar energy per unit area outside Earth’s atmosphere is on the order of ten times that available on Earth’s surface.

Notes

- ^ "Energy Sources: Solar”. Department of Energy. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Cost Of Installed Solar Photovoltaic Systems Drops Significantly Over The Last Decade retrieved 19 May 2009

- ^ Govt to bear 80% cost of generating solar power retrieved 19 May 2009

- ^ In India’s Sea of Darkness: An Unsustainable Island of Decentralized Energy Production retrieved 19 May 2009

- ^ Martin and Goswami (2005), p. 45

- ^ Concentrated Solar Thermal Power – Now Retrieved 19 August 2008

- ^ a b c d "Concentrating Solar Power in 2001 – An IEA/SolarPACES Summary of Present Status and Future Prospects” (PDF). International Energy Agency – SolarPACES. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ "UNLV Solar Site”. University of Las Vegas. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ "Compact CLFR”. Physics.usyd.edu.au. 2002-06-12. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Ausra compact CLFR introducing cost-saving solar rotation features” (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "An Assessment of Solar Energy Conversion Technologies and Research Opportunities” (PDF). Stanford University – Global Climate Change & Energy Project. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ David Shukman (2 May 2007). "Power station harnesses Sun’s rays”. BBC News. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 147

- ^ "”Magic Plates, Tap Sun For Power”, June 1931, Popular Science”. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 18–20

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 29

- ^ Perlin (1999), p. 29–30, 38

- ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p. 63, 77, 101

- ^ "The Solar Energy Book-Once More.” Mother Earth News 31:16-17, Jan. 1975

- ^ Butti and Perlin (1981), p. 249

- ^ Yergin (1991), p. 634, 653-673

- ^ "Chronicle of Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft”. Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ Solar: photovoltaic: Lighting Up The World retrieved 19 May 2009

- ^ "Renewables 2007 Global Status Report” (PDF). Worldwatch Institute. p. 11. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ^ "Global Market Outlook Until 2013” (PDF). European Photovoltaic Industry Association. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ^ a b c d PV Resources.com (2009). World’s largest photovoltaic power plants

- ^ "Enbridge Inc. buys Sarnia solar farm”. Theobserver.ca. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Sarnia Solar Project Celebration”. Enbridge.com. 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Good Energies, NIBC Infrastructure Partners acquire Finsterwalde II and Finsterwalde III”. Pv-tech.org. 2010-10-26. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Implementation of the 39 MWp – „Solar Park Finsterwalde II and Finsterwalde III“” (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "SunEdison sells Europe’s largest solar plant to First Reserve”. Ecoseed.org. 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "First Reserve buys 70 MW solar plant from SunEdison”. Renewableenergyfocus.com. 2010-10-06. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Germany Turns On World’s Biggest Solar Power Project”. Spiegel.de. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Lieberose solar farm becomes Germany’s biggest, World’s second-biggest”. Globalsolartechnology.com. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "PS10”. SolarPACES (Solar Power and Chemical Energy Systems). Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ RSS Feed for Craig Rubens Email Craig Rubens Craig Rubens (2008-08-08). "Abengoa Rakes in $426M for 4 Solar Power Plants”. Earth2tech.com. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Abengoa Begins Operation of 50MW Concentrating Solar Power Plant”. SustainableBusiness.com News. May 6, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "Abengoa Solar begins commercial operation of Solnova 1”. Abengoasolar.com. 2010-05-05. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Abengoa Solar begins commercial operation of Solnova 3”. Abengoasolar.com. 2010-05-24. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Abengoa Solar Reaches Total of 193 Megawatts Operating”. Abengoasolar.com. 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Acciona y ACS inscriben sus termosolares en el registro de Industria”. Cincodias.com. 2009-10-23. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "ACS aumenta un 22,6% las ganancias de su negocio de ‘energía verde’ en la primera mitad de año”. Labolsa.com. 2010-10-08. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "José María Barreda and Ignacio Galán open IBERDROLA RENOVABLES’ first solar termal power plant”. Iberdrolarenovables.es. 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Acciona Status Solarpaces 2008 p.25

- ^ ACCIONA Energía develops 900-million-euro renewables projects in the region of Extremadura[dead link]

- ^ ACCIONA opens its first CSP plant in Spain, in Extremadura[dead link]

- ^ a b "Lokalizacion de Centrales Termosolares de Espana”. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Solar Thermal Power Generation – A Spanish Success Story[dead link]

- ^ "ACS LAUNCHES THE OPERATION PHASE OF ITS THIRD DISPATCHABLE 50 MW THERMAL POWER PLANT IN SPAIN, EXTRESOL-1” (PDF). Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Matters, Energy. "Spain – A Solar Thermal Powerhouse”. Energymatters.com.au. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ "Levelized Cost of New Electricity Generating Technologies” (PDF). Institute for Energy Research. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- ^ Yasu, Mariko, and Maki Shiraki, (Bloomberg) "Silver lining in sight for makers of solar panels", Japan Times, 22 April 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Nellis Solar Power System[dead link]

- ^ "An Argument for Feed-in Tariffs” (PDF). European Photovoltaic Industry Association. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ^ "3rd International Conference on Solar Photovoltaic Investments”. Pvinvestmentconference.org. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Solar Power Services: How PPAs are Changing the PV Value Chain February 11, 2008, retrieved 21 May 2009 [1]

- ^ a b Robert Glennon and Andrew M. Reeves, Solar Energy’s Cloudy Future, 1 Ariz. J. Evtl. L. & Pol’y, 91, 106 (2010) available at http://ajelp.com/documents/GlennonFinal.pdf

- ^ RESOP Program Update[dead link]

- ^ Solar program in Ontario[dead link]

- ^ Proposed Feed-In Tariff Prices for Renewable Energy Projects in Ontario[dead link]

- ^ Mike Hightower, Sandia Laboratories, Renewable Energy Development in the Southwest: Sustainability Challenges & Directions (2009), available at http://www.swhydro.arizona.edu/renewable/presentations /thursday/hightower.pdf.

- ^ Robert Glennon and Andrew M. Reeves, Solar Energy’s Cloudy Future, 1 Ariz. J. Evtl. L. & Pol’y, 91, 109-116 (2010) available at http://ajelp.com/documents/GlennonFinal.pdf

- ^ Carr (1976), p. 85

- ^ Wind + sun join forces at Washington power plant Retrieved 31 January 2008

- ^ "The Combined Power Plant: the first stage in providing 100% power from renewable energy”. SolarServer. January 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ^ "Advantages of Using Molten Salt”. Sandia National Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ "PV Systems and Net Metering”. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ "Pumped Hydro Storage”. Electricity Storage Association. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ Collings AF, Critchley C. Artificial Photosynthesis. From Basic Biology to Industrial Application. Wiley-VCH. Weinheim (2005) p x.

- ^ MSU-CSET Participation Archive with notation in the Murray Ledger & Times

- ^ Layton, Julia (2008-11-05). "What is a luminescent solar concentrator?”. Science.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2011-04-19.

- ^ Perlin and Butti (1981), p. 73

- ^ Halacy (1973), p. 76

- ^ Tritt (2008), p. 366–368

References

- Butti, Ken; Perlin, John (1981). A Golden Thread (2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology). Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-24005-8.

- Carr, Donald E. (1976). Energy & the Earth Machine. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06407-7.

- Halacy, Daniel (1973). The Coming Age of Solar Energy. Harper and Row. ISBN 0-380-00233-7.

- Martin, Christopher L.; Goswami, D. Yogi (2005). Solar Energy Pocket Reference. International Solar Energy Society. ISBN 0-9771282-0-2.

- Mills, David (2004). "Advances in solar thermal electricity technology”. Solar Energy 76 (1-3): 19–31. doi:10.1016/S0038-092X(03)00102-6.

- Perlin, John (1999). From Space to Earth (The Story of Solar Electricity). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01013-2.

- Tritt, T.; Böttner, H.; Chen, L. (2008). "Thermoelectrics: Direct Solar Thermal Energy Conversion”. MRS Bulletin 33 (4): 355–372.

- Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. Simon & Schuster. p. 885. ISBN 978-0-671-79932-8.

- Wikipedia